Geological Fieldwork: Planning, Equipment, Safety

Geological Fieldwork is a critical component of geology that involves studying Earth's materials, structures, and processes in their natural environment. It provides firsthand observations and data that are essential for understanding geological history, resource exploration, hazard assessment, and environmental management.

Fieldwork Planning

Why are you doing it? Are you going as a general exploration or do you have definite reason? Your motives will affect the preparation and the items you will need to take. Where are you going? Do you need permission of the landowner in advance? What are the potential hazards that you are likely to encounter?

Purpose of Geological Fieldwork

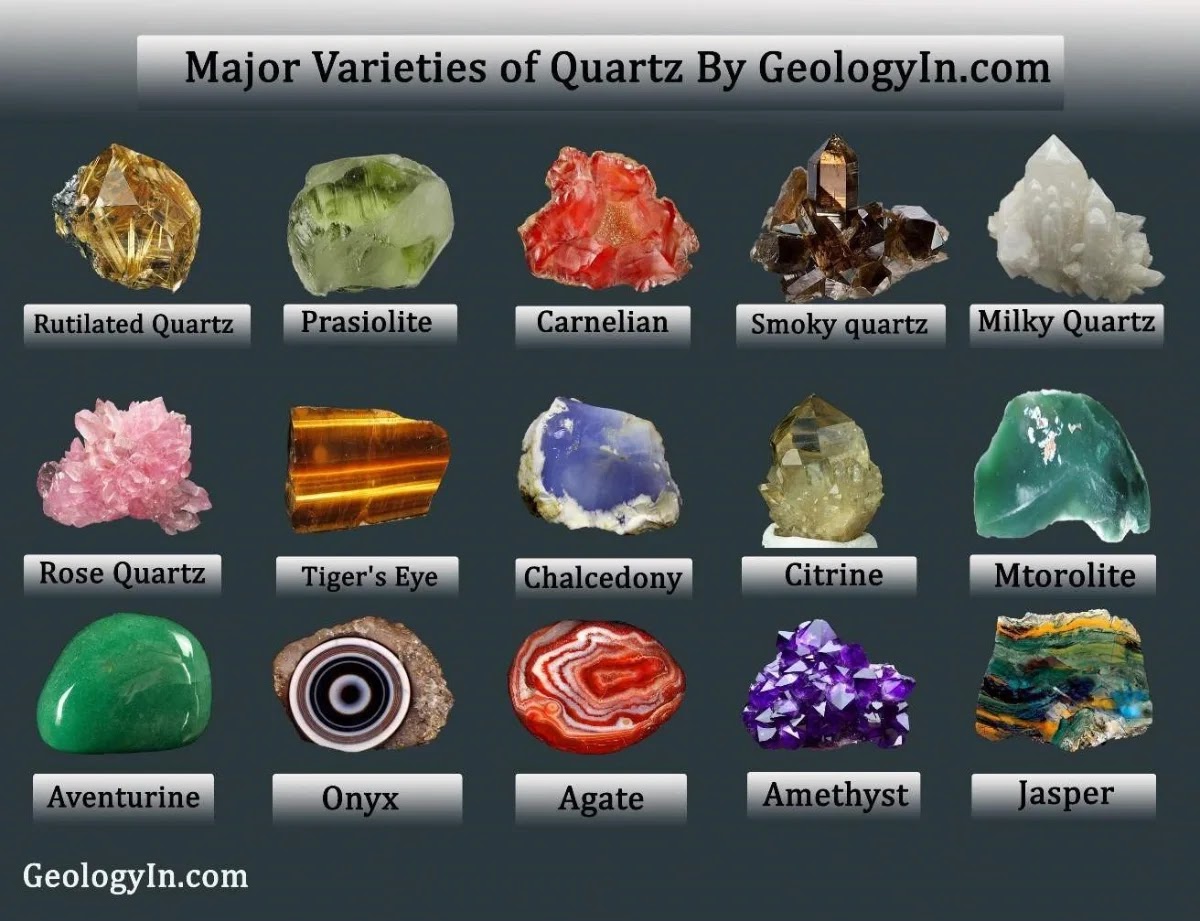

Data Collection: Gathering rock, mineral, fossil, and soil samples for laboratory analysis.

Mapping: Creating geological maps that show the distribution of rock units, structures, and features.

Stratigraphy: Studying rock layers (strata) to understand their sequence, age, and depositional environment.

Structural Analysis: Investigating folds, faults, and other deformational features to reconstruct tectonic history.

Resource Exploration: Identifying and assessing mineral, oil, gas, and groundwater resources.

Hazard Assessment: Evaluating risks from earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions, and other geological hazards.

Environmental Studies: Monitoring and mitigating the impacts of human activities on the Earth's surface and subsurface.

Clothing and Safety Gear for Fieldwork

Proper clothing and safety equipment are essential for a successful and safe fieldwork experience. The right gear ensures comfort, protection, and preparedness for varying weather conditions and terrains. Here’s a detailed guide:

Clothing

Weather-Appropriate Clothing:

- Dress in layers to adapt to changing weather conditions.

- Use moisture-wicking base layers, insulating mid-layers, and waterproof outer layers.

- Avoid cotton, as it retains moisture and can lead to hypothermia in cold or wet conditions.

Footwear:

Choose footwear based on the terrain:

- Wellies (Rubber Boots): Ideal for muddy or wet sites.

- Non-Slip Shoes: Essential for slippery rocks or coastal areas.

- Comfortable Walking Boots: Necessary for long distances or rugged terrain.

In working quarries, safety footwear with steel toecaps is often required.

High-Visibility Clothing:

- A statutory requirement in some working quarries and highly recommended in remote areas to ensure visibility.

- Brightly colored vests or jackets are ideal.

Headwear:

- A hard hat is mandatory in working quarries and on most organized trips. It’s also good practice near coastal cliffs or in areas with falling debris.

- A wide-brimmed hat or cap can protect against sun exposure.

Eye Protection:

- Impact-Resistant Glasses or Goggles: Essential when hammering rocks to protect against flying debris.

- Dark Sunglasses: Useful for studying reflective surfaces like chalk on sunny days.

Avoid Bright Colors in Certain Seasons:

In late spring and early summer, avoid wearing yellow clothing, as it can attract swarms of small black bugs that mistake it for flowering rapeseed fields.

Emergency and Safety Gear

First Aid Kit:

- Carry a basic first aid kit with bandages, antiseptic wipes, pain relievers, and any personal medications.

- Include items for treating blisters, cuts, and insect bites.

Warm Clothing and Emergency Shelter:

- Pack extra warm clothing (e.g., a fleece or thermal jacket) in case you get stranded overnight.

- A couple of dustbin liners (large plastic bags) can serve as emergency rain ponchos or insulation to keep you dry and warm.

Whistle:

A loud whistle can help attract attention if you need assistance in remote areas.

Other Essentials:

- Map and Compass: Even if you have a GPS, these are reliable backups.

- Headlamp or Flashlight: With extra batteries for visibility in low-light conditions.

- Snacks and Water: Stay hydrated and energized during long days in the field.

Geological Fieldwork Safety

Safety is a top priority during geological fieldwork. Whether you’re working alone, in remote areas, or in active quarries, following these guidelines will help minimize risks and ensure a successful trip:

Working Alone: Always inform someone of your plans, including your location and expected return time. Carry a fully charged phone or GPS device, and consider using a satellite communicator in remote areas.

Coastal Work: Check tide tables before heading out and plan your work around a falling tide. Keep an eye on the tide and weather, as conditions can change quickly. Identify exit routes in case the tide cuts off your path, and avoid slippery or unstable areas.

Remote Areas: Check the weather forecast and pack appropriately for the conditions. Carry extra supplies, a first aid kit, and emergency gear like a whistle, space blanket, or large plastic bag. Share your itinerary with someone and stick to your plan.

Working Quarries: Report to the site office upon arrival and follow all safety instructions. Wear required gear, such as a hard hat, steel-toe boots, and high-visibility clothing. Avoid restricted areas and maintain a good relationship with quarry staff to ensure future access.

General Tips: Stay aware of hazards like unstable terrain or falling rocks. Use tools safely, wear protective gear, and take regular breaks. Carry plenty of water and snacks to stay hydrated and energized.

By planning ahead and prioritizing safety, you can reduce risks and make the most of your fieldwork experience!

|

| Tools and Equipment for Geological Fieldwork. |

Tools and Equipment for Geological Fieldwork

Geologists rely on a variety of tools and equipment to conduct fieldwork effectively and safely. Below is a detailed list of essential items and tips for their use:

Essential Tools

Field Notebook:

- Your most important piece of equipment! Always record observations, sketches, and measurements in real-time—do not rely on memory.

- Use a pencil (not a pen) so you can write in wet conditions.

- Carry a large, clear plastic bag to protect your notebook in the rain while allowing you to write.

Geological Hammer (Rock Hammer):

Used to break rocks and expose fresh, unweathered surfaces for examination.

Safety Tips:

- Always wear safety glasses or goggles when hammering.

- Ensure no one is standing nearby when you swing the hammer.

- Never hammer under an overhang or use the hammer as a chisel (hardened steel can splinter).

Think carefully before hammering or collecting specimens. Use fallen blocks or scree whenever possible to avoid damaging exposed rock faces.

Cold Chisel:

- Useful for extracting fossils or delicate specimens from rocks.

- Always use a chisel instead of a hammer for precision work.

Hand Lens (Loupe):

A magnifying lens for close examination of mineral grains, textures, and small-scale structures.

Compass-Clinometer:

Combines a compass and clinometer to measure the strike (orientation) and dip (angle) of rock layers, as well as slopes.

GPS Device:

For precise location mapping and navigation in the field.

Tape Measure:

Used to measure the thickness of rock beds or the size of geological features.

Sample Bags and Labels:

- Self-seal plastic bags are suitable for most rock samples, while tough cloth bags are better for sharp or heavy specimens.

- Label each bag with location, date, and description, and include a written note inside the bag for added security.

- Wrap delicate specimens in newspaper for protection.

Trowel:

Useful for collecting samples from soft rocks like clay or unconsolidated sediments.

Optional but Useful Equipment

- Camera: For documenting outcrops, structures, and samples with photographs.

- Topographic Maps and Aerial Imagery: For navigation and contextual understanding of the study area.

- Field Guides and Reference Materials: Books or charts to help identify rocks, minerals, and fossils on-site.

Safety Gear

Helmet: Protects against falling rocks or debris.

Gloves and Boots: Essential for working in rugged or hazardous terrain.

First Aid Kit: For treating minor injuries in the field.

High-Visibility Clothing: Especially important when working near roads or in remote areas.

Steps in Geological Fieldwork

Field Observations:

- Identify and describe rock types, minerals, and fossils.

- Measure and record structural features (e.g., strike, dip, fault orientations).

- Document landforms, erosion patterns, and other surface features.

Sampling:

- Collect representative rock, soil, and water samples for laboratory analysis.

- Label and catalog samples with location, date, and description.

Mapping:

- Create detailed geological maps showing rock units, structures, and features.

- Use symbols and colors to represent different geological elements.

Data Analysis:

- Interpret field data to reconstruct geological history and processes.

- Integrate field observations with laboratory results and remote sensing data.

Reporting:

- Prepare reports, maps, and presentations to communicate findings.

- Share results with stakeholders, policymakers, and the scientific community.

Challenges in Geological Fieldwork

- Terrain: Working in remote, rugged, or inaccessible areas can be physically demanding.

- Weather: Fieldwork is often conducted in extreme weather conditions, from deserts to polar regions.

- Safety: Risks include rockfalls, wildlife encounters, and exposure to hazardous materials.

- Logistics: Transporting equipment and samples can be challenging in remote locations.

When You Return

Once you’re back, notify the person you informed about your plans that you’ve returned safely. This prevents unnecessary worry and avoids triggering emergency responses like search parties or memorial lectures!

Afterward, unpack your samples and ensure they’re properly labeled with location, date, and description. Review your field notebook and add any missing details while the information is still fresh. If you created graphic logs or took measurements, make neat copies of these records to ensure accuracy.

Finally, write a thank-you letter to the site owner or manager. Include a summary of your findings or offer to share any publications resulting from your visit. Maintaining a positive relationship with landowners can lead to future access opportunities and fosters goodwill toward the geological community.

%20(1).webp)