Geologists solve mystery of the Colorado Plateau

|

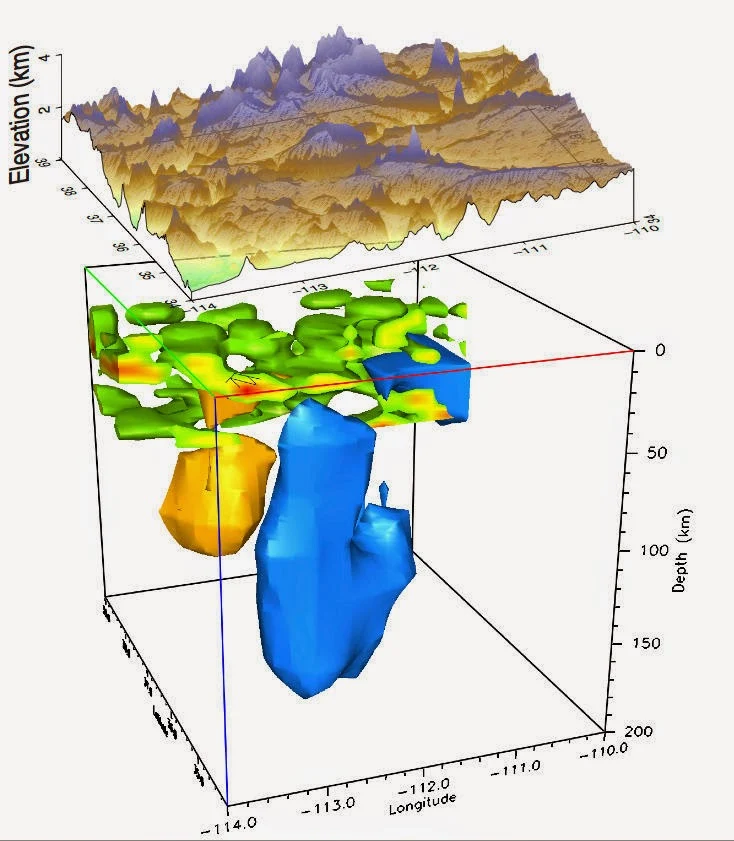

A convective "drip" of lithosphere (blue) below the Colorado Plateau is due to delamination caused by rising, partially molten material from the asthenosphere (gold), as plotted by Rice University researchers and their colleagues and described in a new paper in the journal Nature.

|

team of scientists led by Rice University has figured out why the Colorado Plateau -- a 130,000-square-mile region that straddles Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico -- is rising even while parts of its lower crust appear to be falling. The massive, tectonically stable region of the western United States has long puzzled geologists.

A paper published in the journal Nature shows how magmatic material from the depths slowly rises to invade the lithosphere -- Earth's crust and strong uppermost mantle. This movement forces layers to peel away and sink, said lead author Alan Levander, professor and the Carey Croneis Chair in Geology at Rice University.

The invading asthenosphere is two-faced. Deep in the upper mantle, between about 60 and 185 miles down, it's usually slightly less dense and much less viscous than the overlying mantle lithosphere of the tectonic plates; the plates there can move over its malleable surface.

But when the asthenosphere finds a means to, it can invade the lithosphere and erode it from the bottom up. The partially molten material expands and cools as it flows upward. It infiltrates the stronger lithosphere, where it solidifies and makes the brittle crust and uppermost mantle heavy enough to break away and sink. The buoyant asthenosphere then fills the space left above, where it expands and thus lifts the plateau.

Levander and his fellow researchers know this because they've seen evidence of the process from data gathered by the massive USArray seismic observatory, hundreds of observatory-quality seismographs deployed 45 miles apart in a mobile array that covers a north/south strip of the United States. The seismographs were first deployed in the West in 2004 and are heading eastward in a 10-year process, with each seismograph station in place for a year and a half. Seismic images made by Rice that are analogous to medical ultrasounds were combined with images like CAT scans made by seismologists at the University of Oregon; the resulting images revealed a pronounced anomaly extending from the crust well into the mantle.

Levander said the combined Colorado Plateau images show the convective "drip" of the lithosphere just north of the Grand Canyon; the lithosphere is slowly sinking several hundred kilometers into the Earth. That process may have helped create the canyon itself, as lifting of the plateau over the last 6 million years defined the Colorado River's route.

Levander said USArray has found similar downwellings in two other locations in the American West; this suggests the forces deforming the lower crust and uppermost mantle are widespread. In both other locations, the downwellings happened within the past 10 million years. "But under the Colorado Plateau, we have caught it in the act," he said.

"We had to find a trigger to cause the lithosphere to become dense enough to fall off," Levander said. The partially molten asthenosphere is "hot and somewhat buoyant, and if there's a topographic gradient along the asthenosphere's upper surface, as there is under the Colorado Plateau, the asthenosphere will flow with it and undergo a small amount of decompression melting as it rises."

It melts enough, he said, to infiltrate the base of the lithosphere and solidify, "and it's at such a depth that it freezes as a dense phase. The heat from the invading melts also reduces the viscosity of the mantle lithosphere, making it flow more readily. At some point, the base of the lithosphere exceeds the density of the asthenosphere underneath and starts to drip."

Levander said the National Science Foundation-funded USArray is already providing a wealth of geologic data. "I have quite a few seismologist friends in Europe attempting to develop a EuroArray, one of whom said, 'Well, it looks like you have a machine producing Nature and Science papers.' Well, yes, we do," he said. "We can now see things we never saw before."

Co-authors of the paper are Cin-Ty Lee, associate professor of Earth science, and graduate student Kaijian Liu, both of Rice; Eugene Humphreys, professor of geophysics, and graduate student Brandon Schmandt of the University of Oregon; former Rice postdoctoral researcher Meghan Miller, now an assistant professor of Earth sciences at the University of Southern California; and Professor Karl Karlstrom and graduate student Ryan Crow of the University of New Mexico.

National Science Foundation EarthScope grants and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Research Prize to Levander funded the research.

The above story is based on materials provided by Rice University. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

%20(1).webp)